Are Fermented Foods Good for You?

Are fermented foods good for you? Fermented foods have become increasingly popular in the last few years. And they have been heavily promoted to improve gut health, reduce inflammation, boost immunity, and even help with weight loss.

But are these claims true? Are fermented foods healthy?

Let’s take a close look at what fermented foods really are and their long-term effects on health.

Dangers of Fermented Foods

During the fermentation process, microorganisms convert carbohydrates into alcohol or acids. The acids and alcohol are what give fermented foods their distinctive flavor.

When foods ferment, waste products are produced by the bacteria that break down the food. These waste products are toxic to the body. They are also damaging to the liver and kidneys since these organs have to rid the body of the waste products. The toxins make the blood impure and act on the neurotransmitters in the central nervous system (which in turn impairs functioning of prefrontal cortex and can cause depression).

These toxic byproducts include alcohol, ammonia, acetic acid, lactic acid, aflatoxins, ethyl carbamate, and others.

Amines in Fermented Foods

When protein-containing foods age or are fermented by bacteria, biogenic amines (such as histamine, tyramine, tryptamine, phenylethylamine, etc.) are formed. This overdose of amines has some negative effects on the body and the brain.

When consumed, these amines dilate the blood vessels in the gut. The increased blood flow to the gut can speed up digestion (which gives a feeling of increased energy), but the increased blood flow also inflames and irritates the digestive system. And many amines can cause an imbalance of gut bacteria.

In addition, the extra blood flow to the gut diminishes blood flow elsewhere, thus compromising the health of other body organs.

The amines are then absorbed through the lining of the intestinal tract and into the bloodstream, thus affecting other areas of the body.

Amines are especially irritating to the nervous system and negatively affect the brain cells and other nervous tissue, which can manifest itself as “brain fog”. Consequently, thinking processes, learning, and memory consolidation are inhibited.

The amines constrict the aorta and coronary arteries, have a negative effect on the liver and kidneys, and can also cause headaches or migraines.

In addition, amines disrupt hormonal balance, which can result in anxiety, sleep disorders, and fatigue.

Amines accumulate as the food ages.

The effects of consuming amines are not immediate but rather cumulative, so it can be difficult to notice the association between certain foods and our symptoms.

Aflatoxins in Fermented Foods

The fermentation process also creates aflatoxins. Aflatoxins negatively affect all the body’s organs, especially the liver and kidneys, and can contribute to the development of autoimmune diseases and cancer.

Acetaldehyde in Fermented Foods

Acetaldehyde is another one of the byproducts of the fermentation process.

The consumption of acetaldehyde causes a deficiency in vitamin B1. Vitamin B1 is essential for healthy brain and nervous system function. It promotes emotional stability and helps us focus and learn, and it helps strengthens the memory. A deficiency in B1 can lead to depression, fatigue, irritability, and other health issues.

Acetaldehyde also alters red blood cell structure and causes the membranes of red blood cells to become stiff, making it difficult for them to transport oxygen (which is their main function). When this happens, many of the body and brain cells do not receive the oxygen they need, and some may even atrophy and die.

Acetaldehyde can cause degeneration of dendrites in the brain. This, in turn, may lead to hippocampal atrophy; in Alzheimer’s disease, the hippocampus is one of the first regions of the brain to be affected.

Glutamate in Fermented Foods

Glutamate is another byproduct of the fermentation process. Excess glutamate in the body overstimulates nerve cells, which causes them to fire too rapidly and can lead to extreme exhaustion and often death of the nerve cell.

Fermented Foods and Cancer

Research shows that the consumption of fermented foods increases one’s risk for cancer. One study showed that replacing unfermented soy foods with fermented soy foods increased the risk of cancer by 58%. In another study, increasing consumption of pickled foods was associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer.

Fermented Foods and Cravings and Weight Gain

Fermented foods can cause cravings and increase appetite. Caloric intake tends to increase by up to 30% for at least 24 hours after eating fermented foods.

Antibiotic Resistance and Fermented Foods

When a food is fermenting, bacteria, molds, yeasts, and viruses multiply in the food, and fermented foods often contain viral DNA sequences from unidentified viruses. Many of these viruses carry genes that confer resistance to antibiotics.

Fermented Foods Are Low in Nutrients

Fresh and unprocessed foods are those that are highest in nutrition. As a food ages, it loses nutrients.

Adrenal Function and Fermented Foods

Fermented foods can also impair adrenal function and are damaging to the pancreas islets and myocardium.

Fermented Foods and Gut Health

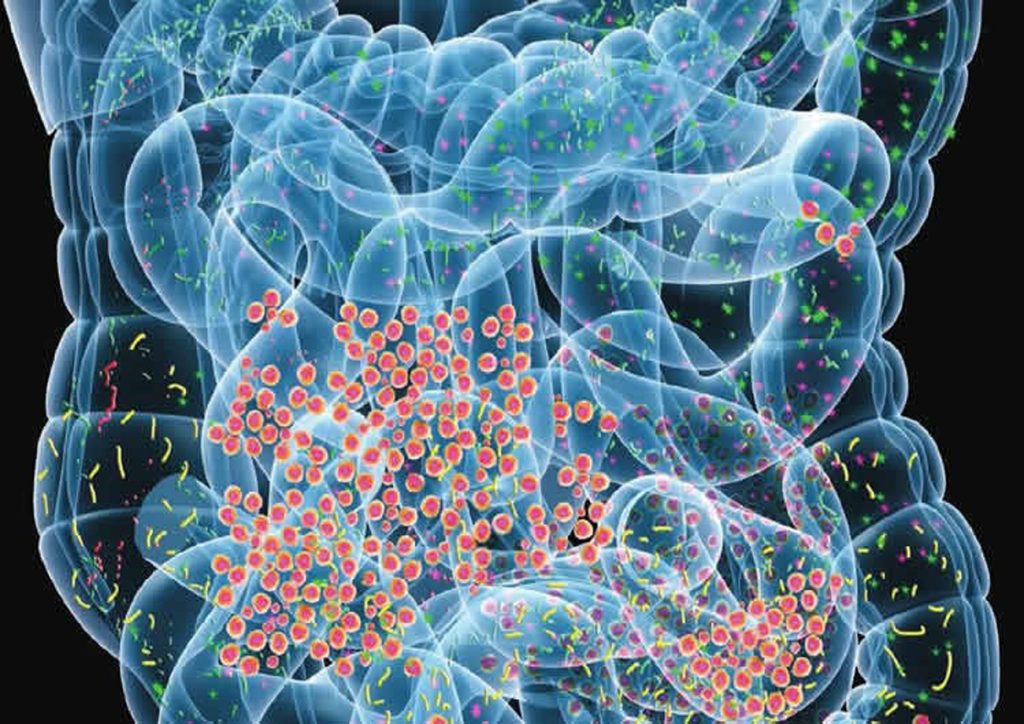

The gut microbiome contains tens of trillions of microorganisms. These include up to 1,000 different species of bacteria with over 3 million genes. Gut microbiomes are as individual as fingerprints. Each and every person has a very individualized and precise combination of microbes unique to their own body needs, environment, lifestyle habits, and experiences.

The body is constantly working on creating the proper balance of bacteria in the gut, adjusting the combination and balance of microbes continually to meet the needs of the body according to its current environment. It also adjusts according to the foods an individual generally eats. (Certain foods need certain bacteria for proper digestion.)

With proper health habits, this continual adjusting process keeps the microbes in the perfect balance to meet the body’s needs. But introducing fermented foods or probiotics into this precise system alters the balance of microbes and upsets the individualized balance of bacteria and can hinder the body’s efforts to adjust to the needs of the system. Instead of helping to balance gut microbiota, fermented foods and probiotics actually delay the re-balancing of gut microbiota.

“Because of the intricate balance that exists within the microbiota, alterations in one group or species may not only affect the host directly, but can also disrupt the entire microbial community.” Nutrients 2012

In the process of fermentation, not only are good bacteria developed, but bad bacteria and yeast also grow. The fermentation process is a case of survival of the fittest, and often bad bacteria and yeast are more prolific than the good bacteria. This also can throw off gut health.

Studies show that fermented foods and probiotic supplements actually decrease the diversity of participants’ microbiomes.

It’s important to remember that the bacteria in fermented foods and probiotics are living, and once they are in the human system, they can replicate, adapt, or change, or accumulate genetic mutations. But once we introduce these bacteria into our body, we have no control over any of this. New neurochemicals that have not been previously discovered can be produced by certain bacteria. And, the bacteria can acquire the ability and properties that may be damaging to the body and to the health.

“Contrary to the current dogma that probiotics are harmless and benefit everyone, [study] results reveal a new potential adverse side effect of probiotic use” Eran Elinav, an immunology researcher at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel.

So how do you promote gut health?

A whole-food, plant-based diet free from fermented foods and free from refined foods is the very best way to support your body’s natural ability to correct and adjust gut microbe balances and maintain good gut health.

A healthy, plant-based diet can create a gut bacteria diversity and balance like no other diet or supplement can. We do not see a similar gut microbiome in any other type of diet.

“Studies proposed novel microbiome-related pathways, by which plant-based diets modulate the gut microbiome towards a favorable diversity of bacteria species”. Translational Psychiatry 2019

God’s Design

Our Creator designed the human body to thrive on fresh fruit, vegetables, grains, nuts, and seeds. This is made clear in the Bible in the book of Genesis. God says, “I have given you every plant yielding seed [grains] . . . and every tree with seed in its fruit [tree fruit and nuts]” Genesis 1:29 RSV and “the plants of the field [vegetables].” Genesis 3:18 RSV “You shall have them for food.” Genesis 1:29 RSV

“Nicely prepared vegetables and fruits in their season will be beneficial, if they are of the best quality, not showing the slightest sign of decay, but are sound and unaffected by any disease or decay.” Counsels on Diet and Foods 309

The foods that are highest in nutrition are those which are eaten in their fresh, natural, and unprocessed state. The human body was not designed to ever consume rotted or spoiled food.

How to avoid fermented foods

Common fermented foods to watch out for are: beer (and other alcoholic beverages), brown rice syrup, cheese, chocolate, fermented soy, kefir, kombucha, miso, kimchi, Marmite, natto, pickles, Promite, rejuvelac, sauerkraut, sour cream, some sourdough bread, soy sauce, tamari, tempeh, salami, Worcestershire sauce, Vegemite, vinegar, wine, and yogurt.

Research and References

Researchers observed a low prevalence of gastric cancer in subjects with high intake of non-fermented soy foods. On the other hand, increased consumption of fermented soy foods was found to elevate stomach cancer risk in this study. Cancer Science 2011

Researchers found high levels of agmatine in fermented foods and alcoholic beverages, such as wine, beer, and sake. The findings of this review show that high consumption of fermented products and alcoholic beverages pre-disposes an individual to the toxic effects of agmatine. Frontiers in Microbiology 2012

A 2009 meta-analysis examined 34 English and Chinese language studies conducted to examine the connection between lacto-fermented foods and cancer of the esophagus. After reviewing the evidence, the researchers determined that there was double the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma associated with eating lacto-fermented foods.” British Journal of Cancer 2009

“…the results of this meta‐analysis provide evidence that high intake of pickled vegetables was associated with an increased GC (gastric cancer) risk, whereas high intake of fresh vegetables was associated with a decreased GC risk. These results may explain why the GC incidence rates in Japan and Korea remain high despite a high consumption of vegetables in these countries. A high consumption of fresh vegetables, rather than the total amount of vegetables, which includes pickled vegetables, should be promoted to reduce GC rates in Japan and Korea.” – Cancer Science 2010

V. J. Navarro, Huiman Barnhart, Herbert Bonkovsky, Herbal and dietary supplement induced hepatotoxicity in the US, Gastroenterology 2012

Bhagavathi Sundaram et al, Toxins in Fermented Foods: Prevalence and Preventions-A Mini Review. Toxins 2018

Miguel A.Alvareza, et al, The problem of biogenic amines in fermented foods and the use of potential biogenic amine-degrading microorganisms as a solution. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2014

Enrica Pessione, et al., Bioactive Molecules Released in Food by Lactic Acid Bacteria: Encrypted Peptides and Biogenic Amines. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016

Meyer, J. H., et al, Elevated monoamine oxidase a levels in the brain: an explanation for the monoamine imbalance of major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 2006

Vincent Martin, et al, Diet and Headache: Part 1. Headache 2016

Jian-Song Ren, et al. Pickled food and risk of gastric cancer-a systematic review and meta-analysis of English and Chinese literature. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers and Prevention 2012

Duarte-Salles T, et al. Dairy products and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. International Journal of Cancer 2014

Wang C, et al, Case-control study on risk factors of laryngeal cancer in Heilongjiang province. Lin Chuang er bi yan hou tou Jing wai ke za zhi [Journal of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology, Head, and Neck Surgery] 2011

Hyejin Yu, et al, Vegetables, but not pickled vegetables, are negatively associated with the risk of breast cancer. Nutrition and Cancer, 2010

Kirsty Brown, et al, Diet-induced dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota and the effects on immunity and disease. Nutrients 2012

Lawrence A David, Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014

Z. Erginkaya, E. U. Turhan, D. Tatlı, Determination of antibiotic resistance of lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional Turkish fermented dairy products. Iranian Journal of Veterinary Research 2018

Jotham Suez, et al, Post-Antibiotic Gut Mucosal Microbiome Reconstitution Is Impaired by Probiotics and Improved by Autologous FMT. Cell 2018

Nathan Crook PhD, et al, Adaptive Strategies of the Candidate Probiotic E. coli Nissle in the Mammalian Gut, Cell Host & Microbe, 2019

Truss, C.O. Metabolic Abnormalities in Patients with Chronic Candidiasis: The Acetaldehyde Hypothesis. Journal of Orthomolecular Psychiatry 1984

Sorrell, M.F., Tuma, D.J., The Functional Implications of Acetaldehyde Binding to Cell Constituents. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1987

Kim J, et al. Fermented and non-fermented soy food consumption and gastric cancer in Japanese and Korean populations: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Science 2011

Peiwu Li, et al. Aflatoxin Measurement and Analysis, Aflatoxins – Detection, Measurement and Control, Dr Irineo Torres-Pacheco (Ed.), ISBN: 978-953-307-711-6, InTech 2011

Kim YK, et al Determination of ethyl carbamate in some fermented Korean foods and beverages. Food Additives and Contaminants 2000

Hinton DM, et al. Immunotoxicity of aflatoxin B1 in rats: effects on lymphocytes and the inflammatory response in a chronic intermittent dosing study. Toxicological Sciences 2003

Park EJ, et al. Metagenomic analysis of the viral communities in fermented foods. Applied and Environmental Microbiology Journal, 2011

Colombo S, et al. Characterization of airborne viromes in cheese production plants. Applied and Environmental Microbiology Journal 2018

You my also like:

Before you go . . .

Did you know that you can eat all this delicious food AND lose weight? You can!

No calorie counting. No portion sizes.

Join my online weight loss program today!

This is the most helpful article I’ve ever read about fermented foods. Thank you.

You’re welcome, Alina. I’m glad it was helpful.

Your website is full of misinformation and straight bullshit. You’re not qualified to offer diet or health advice.

Hi Jennifer.

I have noticed that you don’t use nutritional yeast in any of your recipes, then came across this article. I was wondering if you could tell me more about your studies in this subject and why you don’t use that ingredient, as I have read it is an inactive form of yeast.

I also was wondering about vegan yogurts as I have learned that they are supposed to help replenish gut microbiome if one, say, needed to take charcoal or antibiotics. I, also, was told by a nutritionist that eating yogurt or other things with the good bacteria is good to eat even at every meal.

You had mentioned “some” sourdough bread. Would you expound on that as well?

And, what about tamari that is made with just water, organic soybeans, salt, and kombu (dried seaweed)?

Thank you! God bless!

Hi Alisa,

Great questions. 🙂

I am writing an article on nutritional yeast and will post it on my website very soon. If you are subscribed to my newsletter, you should see a link to it in there.

Concerning yogurt, studies show that the “active cultures” on yogurt labels does not guarantee that there are any probiotics in the yogurt by the time you eat it. In addition, any sweeteners in the yogurt will negate any benefit as the sweeteners kill beneficial bacteria in the gut.

Research also shows that taking probiotics can actually slow down or inhibit the body’s ability to balance the gut microbiome. I have quite a bit more information on that so I should probably write an article on that subject and post it along with the studies that were done.

In short, the body knows how to balance the microbiome way better than any manufacturing company and the best way to have good gut health is to give your body healthy foods and avoid foods that cause an imbalance (such as sweeteners).

The name “sourdough bread” is given to a wide variety of breads made in a wide variety of ways. Some bread that is called sourdough is made in one way (and the bread truly is sour) and some is made in another way (and the bread isn’t sour).

Bread that tastes sour tastes that way because in the process of making it acetic acid, alcohol, glutamate (a gustatory stimulus), and other toxic by-products of fermentation are produced in the dough.

But what about “sourdough” bread that does not taste sour?

I have researched that subject extensively, and although one can find many health experts (and others) promoting the benefits of sourdough bread, I have not found conclusive, solid, and sound scientific evidence indicating that it is a healthful choice. Because of this, I don’t make a statement either way.

Hope that helps. 🙂

Blessings,

Jennifer

Thank you, Jennifer, for this most informative article on all things fermented. I also appreciate you noting the studies. It’s great to have those when friends ask about the supporting science.

You’re welcome, Dori. I’m glad it was helpful.

Thank you for your comment.

Thank you for your addressing fermented foods

Right now I am consuming PRobotic rich Sourkraut ,kiefer homemade yogurt with lactobacilis ruteri and other keystone strains plus taking akkermansia probiotic that is very expensive.

All this after taking a prescribed Powerful Antibiotic 2 years ago,Blood test says I have Lyme disease So I was prescribed more Supposed 2 months on natural antibiotics, Biosiden because of imbalance of bad over good gut bacteria, and Alimed (very expensive)from concentrated garlic 3 months for Lyme cure.

Since about 2 or 3 years ago I have lost 30 pounds of flesh am now 63yrs old most of my life I was 175 pounds 6 foot tall.

My main income is from long haul truck driving a Unhealthy sedintary occupation.

In the last 2 or 3 years as well began irregular bowel movements according to functional medicine man incomplete digestion and he suggested colonoscapy to check for colon cancer ,what is not goin to happen.so now did 2 weeks ivermectin and fenbendazole what was originally to only be for my livestock and dogs,

And between the wormer and lacto rueteri homemade yogurt my gi issues are subsiding.

The Functional medicine Doctor Wanted to do a gi map sample to a lab before I started ivermectin and fenben ( I did not tell him I was goin to use the wormer ) ,he said h pylori was really bad in me and akkermansia was wiped out in my gut .

I bought a masticating juicer and juice variety of foraged herbs edible weeds and clover,for fresh green chlorifiyl and to supplement nutrition and fiber.

For the last few years I went through much stress emotional mental Even Fell off the wagon for2 yrs again in 2018 I am an alcoholic in recovery by God’s grace.

In 2006 I gave my heart to the Lord was baptized Seems maybe that you are the same ,You quote God’s word and writings of Mrs Ellen G White.and seems you love the Lord and your neighbor as your self, doing medical ministry work.

Anyway my phone battery is about to go dead I am very slow at sending emails I have so much going on here in the last few years that it’s hard to keep things figured out. After a while a person can get overwhelmed.

IVAN TORBECK

Godbless you Jennifer

I’m so sorry you have been through all this suffering, Ivan. I can’t imagine how difficult that must be. I’m thankful you know the Lord – He is the great Physician. And He cares deeply for us.

I hope my website can provide you with help as you navigate your health situation.

Blessings to you,

Jennifer

Hi Jennifer. I appreciate you presenting this less-popular view of fermented foods. I have experienced digestive issues for most of my life, and for a few years I believed the louder voices touting the benefits of fermented foods and probiotics for gut health. However, once I learned how to tap into my body’s intelligence, I was guided to stop consuming ferments. I didn’t understand why, but I knew that was the right thing for me personally. In hindsight, not only did eating those foods not improve my gut health, but I think they also had an addictive quality. They were unappetizing at first, but when I force myself to eat/drink them, I eventually acquired a taste for them and began to crave them. The crave/satisfaction cycle made it easy to convince myself that they were benefitting me. The information you presented here helps me understand why my brilliant body said no.

Do you have suggestions on how to add umami to recipes without miso or nutritional yeast? Thanks!

HI Cary,

Thank you for your comment. yes, fermented foods can be addicting. I’m really glad that you recognized that and are on a better track now.

As far as replacing miso and nutritional yeast, it really depends on the recipe and what are the other ingredients in the recipe. Feel free to look through my recipes on this site. I’ve taken foods (such as vegan cheese and savory spreads) that typically contain miso and/or nutritional yeast and developed recipes that taste good without these ingredients.

And I’m regularly adding more. If you sign up to my New Recipe Newsletter, you’ll get them straight to your inbox.

Take care,

Jennifer